I want a world where movies like Braveheart aren’t old-school

On myth, masculinity, and why we still need cinematic heroes

Braveheart is a classic, it won five Oscars; and, I’m ashamed to admit that I watched it for the first time only last week — especially considering that I lived in Scotland for four years. The reviews of the film are mostly very positive, which is no surprise as it is a widely successful film, both technically and dramatically. Through a cinematography that showcases Scotland’s mesmerising landscapes, hugely impressive combat scenes, and straight to the point acting, Mel Brooks gives his version of William Wallace’s fight for Scottish independence brilliantly. The film’s negative reviews mainly focus on its blatant lack of historicity: the lists of dreadful inaccuracies are endless. Another existing criticism, which I heard my university-educated superego snark as I viewed the film, is that Braveheart is a macho-man’s fever dream that spews out dangerous nationalistic sentiment along with an outdated, diminishing portrayal of women, all to portray a false and caricatural view of masculinity. In short, I doubt a film like this would be very successful today. Gladiator II’s mitigated reviews hint at this. (Personally, I liked it but my reasons are probably not those of the general public, if you know what I mean… #PaulMescalIsAHottie). In fact, most of the negative reviews I’ve read on Gladiator II also focus on what an embarrassment it is to History. But why do people expect these films to be historically accurate? Since when are epic, action-driven tales expected to be realistic?

Braveheart codifies the Mythical and Epic Ethos

It should be instinctive to know that if it is on a screen, it is not real — unless, perhaps, it is a documentary, but even then, each scene is chosen and edited to appear or not. After 130 years of cinema, not to mention the centuries of fictional stories, the distinction between reality and fiction is still poorly drawn. Would this be the source of our issues? I would have expected audiences today to have become disillusioned by the “based on a true story” preface. “Based on a true story” is a dramatic accessory, which presets a particular expectation in audiences and widely influences the way the film is viewed. It will likely give more gravity to a story that might otherwise not be taken as seriously. The Coen Brothers deliberately used this effect in Fargo in order to play with the audience’s expectations and deconstruct the Film Noir genre. If we were to take the Coen Brother’s definition of a “true story” as law, every film would require a “based on a true story” notice in its opening credits since, as we all know, every story is drawn from some lived experience. In the case of Braveheart, there is no opening credit signalling the film’s historical nature, however, we can guess it by the authoritative narrator, who even says ‘historians will say I am a liar’ as he preludes the epic story. The audience is led to assume that this is a historical film, and that it must, therefore, be historically accurate. Perhaps, infected by contemporary sloth, they see the film as what could replace a history lesson.

Of course, nothing about the film is historically accurate, nor should it be. The screenplay for the film was written by Randall Wallace, a Russian literature graduate — not a historian— after a trip to Scotland intended to learn more about his Scottish roots. In other words, the film is a romanticized dramatization of William Wallace’s life, which undoubtedly was worthy of a Hollywood production. The mise-en-scène, which is judged as ridiculously ahistorical and could only appeal to a male audience, is in fact a perfect rendition of this romanization and is truly faithful to the genre of the film. Kilts did not exist at the time, neither did blue face paint, and the French queen of England was never and would never have carried William Wallace’s child — of course not! These are simply elements that contribute to a visual world which is essential to the recognition and understanding of the film. In fact, by adding such romanticized iconography to the film, Mel Gibson adheres to a very medieval genre — le roman gallant, or the chivalrous novel.

Through its anachronisms, Gibson’s mise-en-scène is faithful to 12th century European narrative traditions and successfully codifies modern myth-building. The novel as we know it today, written in vernacular prose and with an omniscient or varying narrator originated in the 12th century “romans” which referred to books that would be translated to a vernacular prose in Medieval France. Around that time, Chrétien de Troyes in France and Geoffrey of Monmouth in England were writing those novels. Their favorite topics? Valiant knights slaying dragons, fighting for justice and saving princesses. Though Braveheart is a Scottish story, its lore reflects a highly Arthurian aesthetic and revives the tropes of chivalry in a similar way as Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe. If the film were historically accurate, it would lose its romantic charm, and would prevent it from being a “classic”, or in other words, a cinematic myth. Myths were never meant to be realistic or accurate, they were meant to teach us values through our most precious human tool — imagination.

The death of Myths and Epic Adventure Tales

The prevalent expectation of historical accuracy and realism in general in works of fiction such as Braveheart or Gladiator II only shows how cynical this generation has become and little power myth has over society today. The power of a great myth or legend is unraveling how a person (including hobbits), sometimes with no great qualities or powers, manages to go through life’s trepidations and face multiple challenges through the sheer power of courage and with one goal in mind: the greater good. Without courage, there is no story. Myths can be fantastic or realist, it doesn’t really matter, as long as there is an active sense of the sublime that emerges from the atmosphere and characters of the story. In the end, the protagonist must transform into something greater than himself, a true hero to be remembered and, more importantly, to be admired. Heroes set the example, especially for men. Most of the myths that have shaped society were “based on a true story”. The story of Gilgamesh, The Iliad and Odyssey, even King Arthur, all used the label of History to legitimize their tales. Would we assume ten-headed snakes roamed in the seas and one-eyed giants lived in caves back in the day? So, why should we expect the story of William Wallace to be any more “accurate”? Just like the fantastical creatures in those aforementioned myths, the historical inaccuracies in Braveheart serve the epic genre in an essential way. It is clear that, today, the epic genre is dead. Audiences are no longer impressed, no longer project themselves in these heroes and therefore no longer value the ideals those heroes fought for, and which their authors painstakingly communicated to us.

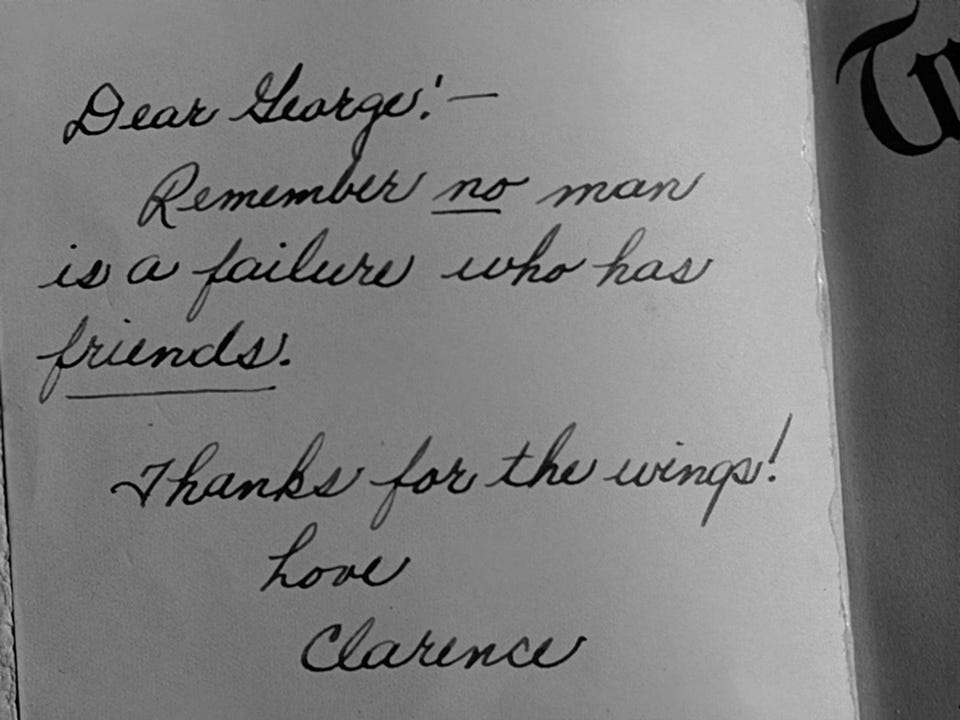

The fall of the Epic will have terrible societal consequences, if these haven’t already started. We learn through imitation, and for centuries epic adventure stories, whether based on history or not, were educating young boys on values such as courage, justice, faith, resilience, loyalty and friendship. In this sense, characters like Tom Sawyer, Harry Potter, Percy Jackson, etc. count as heroes just as much as William Wallace does. But reading is not so popular anymore, and the argument that Marvel heroes represent the new American myth is quickly dismantled by the fact that these are superheroes, not human beings. We can look to say “if he can do it, why can’t I?” When the Epic genre is taken away from boys, along with its adventurous fantasy which catalyzes great (and necessary) imagination, where do these young men go for their daily dose of masculinity? I believe his name is Andrew Tate. This is clearly a dramatic jump in reasoning, however, I believe, not so far from the truth.

Who fills the void when Heroes are gone?

Great Men narratives such as Braveheart strive to create … great men. Watching Braveheart will not necessarily make a better man, nor is it a green flag if your new boyfriend loves Braveheart. Rather, films like Braveheart satisfy the masculine urges of action-packed violence but with actually sustainable and good values. The message of Braveheart is not “be super jacked and kill a bunch of English pricks”, it’s “fight for what you believe in, the freedom of your people from unjust tyranny, no matter the cost, no matter how much money anyone offers you, no matter whether you’ll be quartered and displayed on the all corners of the country.” Exaggeration, dramatization, being “cheesy” or “cringe” is necessary in these narratives, because the hero fights against all odds and expectations, does not stoop down to what is cool or what people might say of him. Braveheart, like Gladiator, teaches that the most important strength is moral, not physical. In fact, it’s one of the first things William Wallace learns when his uncle tells him, "First, learn to use this... (points to head) then I’ll teach you to use this." (holds up sword). Men are more concerned with their looks now than ever before. One moment that struck me in the Netflix show Adolescence, which touches upon the subject of masculinity so brilliantly, was when Jamie, the protagonist, said girls would never love him because “he’s ugly.” Looks, just like physical strength, are only a secondary, if not completely irrelevant, factor in any of the mythical heroes' lives, yet now they have become the main objective for validation and self-confidence. The objectives for men have shifted from moral valour to superficial, narcissistic ideation.

No matter how many videos we watch on the omnipresence and potency of the algorithm, we are not genuinely aware of how brainwashed we truly are. As a woman, I am deeply concerned by the rise of incels, the disturbing rhetoric against women, the growing public violence, not just against women but of innocent children, and the visible divide between the sexes. It seems we are all utterly lost in translation. Our screens feed us illusions of the greater good, grandiose ideas of self-realization and perfection, promoting lifestyle changes that will make everything better. Gym routines, intricate diets, face massage, looks-maxxing, all these recipes for perfection dictated by influencers — sexual desirability and popularity are all the easiest gaps to fill. Being a good, virtuous person is much more challenging. On the other hand, those influencers who preach more “traditional” values are in fact misogynistic and hateful perverts who influence young men into becoming violent predators. Either way, everything is politicized, even content that does not intend to be will be categorized on the political spectrum. Films, stories offer a world beyond the one we live in, in which our imagination can run wild and therefore where we can think for ourselves. Our imagination might be influenced by what we see, but it is our own individual power. Being “realistic” or striving for accuracy and realism in the only space where we are allowed to be inaccurate and ridiculous, that is, in works of fiction, prevents us from striving for something beyond this physical world. Films like Braveheart, teach us to be brave, to have the courage to go against the grain, and to be loved for it.

I was having a very similar conversation recently on the podcast around the idea of historical authenticity in film, specifically in reference to The Doors. One of our guests recounted an anecdote involving Ray Manzarek and Robby Krieger (the keyboard player and guitarist of the band). Apparently, during an interview, one of them was asked if they remembered writing Light My Fire, and he began describing a scene in which Krieger plays the melody for the band, then Manzarek says, “Go have a walk on the beach while I figure out the intro.” Cut to: a fully formed version of the song. After listening to this retelling, the other band member interjected, “That’s not what happened — that was the film.”

It’s a perfect illustration of cinema's ability to ingrain in the cultural psyche a historiography of the past. These representations, filtered through affective narrative and formal stylisation, often become the dominant way a historical moment or figure is remembered, over and above the actual events. This blurring of representation and memory is a recurring by-product of 20th-century visual culture, and arguably, it intensifies in the digital era where myth and meme operate symbiotically.

Your piece also eloquently raises the increasingly urgent question: what does "positive" or "aspirational" masculinity look like today? It feels too reductive to say that the traditional heroic model is simply toxic and must be discarded. What’s more interesting is how those earlier archetypes, the ‘Great Man’ figures, the stoic martyrs, now have to be shot through with ironic self-awareness or existential doubt. The modern hero has to apologise for being a hero because heroism can not be considered a "pure" quality any more.

We see this reflexivity everywhere: in Marvel’s quippy undercutting, in the brooding trauma of The Batman, even in the self-loathing of prestige TV protagonists. Strength is no longer purely physical or moral — it’s emotional literacy, vulnerability, self-interrogation. But here’s the rub: if the traditional epic myth becomes culturally untenable, yet no new myth has been established to take its place, then the vacuum gets filled — often by online avatars of masculinity that thrive on grievance and spectacle.

There’s something to be said for the return of earnestness, even mythic excess. I’d argue that Braveheart (and even Gladiator) are useful not for what they say about history, but for how they channel the need for transcendence, that mythic register where courage, sacrifice, and moral conviction are stylised into forms of cultural aspiration. And while it's easy to mock the slow-motion battle cry or the swelling score, there’s a reason those tropes endure, they speak to a elemental human feeling.

I'm loathed to mention it but this is why spectator sports are so enduring. I was up until 1 am watching Rory McElroy win the Masters. It not exactly Mel Gibson crying freedom, but it was a story of vanquishing ones own demons and writing your name in history.

The cultural problem isn’t necessarily that we make films like Braveheart, it’s that we don’t know how to read them anymore. We demand realism from works whose power derives from romantic symbolism. Or worse, we discard them because their formal excesses don’t conform to current ideological tastes. In doing so, we risk flattening culture into the palatable and didactic.

I think your final point is especially astute: if we strip fiction of its capacity to exaggerate, imagine, or mythologise, we diminish our collective capacity for moral and emotional projection. Perhaps the issue isn’t that epic myths are dead, it’s that we’ve lost the interpretive frameworks to understand what they’re for.

Very interesting essay! I liked how you explained the utility of myths for boys and how the updated idea of hero is twisted... Now I want to see this movie hhhhhh😂