The honest truth about working for my dad

My first months as Saint Clair Cemin’s studio manager

This week will mark my 6 months working for my father, Saint Clair Cemin, a Brazilian sculptor whose career spans over 40 years. Just a year ago, I would’ve never thought to be in this position, and I’m surprised to say I am happier now than I could have imagined.

Last year, I was working at an important indie film production company in Paris, dreaming of one day becoming a filmmaker. These dreams are not entirely gone, but let’s say they’ve matured. As a production assistant, I was able to see how the dreams I had built over my years as a story-obsessed theater kid were actually made. Though we sometimes get to go to Cannes or Berlin and meet with fascinating artists, working in production, as exciting and glamorous as it may be, is as corporate a job as any other. However, it’s fair to say that it is an especially challenging and often underappreciated career. Without even mentioning how incredibly competitive that job market is, working as a set technician or within the production team is the best training for the school of life and any future career. It requires an immense attention to detail, a great level of emotional intelligence, patience, skills for convincing people to give you a lot of money for very little return, balancing a thousand things at the same time and dealing with the most dire and yet sometimes ridiculous emergencies without a sweat. I didn’t expect all these aspects of my previous job to be so easily applicable to my current one.

Neither did I ever expect that I would work for my dad. Not because I don’t like him or his work, but because I didn’t really see at as an option — in fact, I never really saw my dad’s work as a job. When I was a child, I never thought twice about my father’s career choice. He was just my dad, and once in a while he would have a show and apparently that was a big event. I only understood quite late, perhaps in my last years of high school, what his profession entailed, how successful and renowned he actually was. The realization came when he spent nearly two years building a marble boat (that can acutally float) called Psyche, which was shown at the Paul Kasmin gallery in 2016, almost exactly 9 years ago. My mother had even made a documentary about it, filming the whole process — from choosing the marble in a quarry in China to its final installation at the Rowdy Meadow sculpture park in Ohio. I’ll never forget the night of the opening. It was the same night some girl at my high school was celebrating her sweet sixteen in Chelsea. After the opening, I joined the party, which, like all parties organized by Upper East Side helicopter moms, was ostentatious for the sake of Instagram. On our way home with two girlfriends, the cab passed in front of the Kasmin gallery and I said “Hey look, that’s my dad’s sculpture”, and one of the girls answered “What, this huge bathtub?”. I was extremely offended and told her off as well as a conflict-avoider can.

Who could blame the girl — sixteen, drunk on Malibu, just trying to have a good time? Yet, in that moment, I came to realize that I had taken my whole life for granted. Perhaps my parents had been too humble, or else made sure to prevent any potential arrogance in my character; whatever the case, they never made my father’s career the main subject of my identity. Of course, it his career played an important role in my upbringing: I was surrounded by artists, (I remember washing Ron Gorchov’s paint brushes when I was just a girl), went to galleries and museums every week, had a solid knowledge art history without ever really thinking much about it. The art world was simply our world; and yet my parents never made it a thing. I also didn’t have any conception of how my father actually worked. Often he would disappear to China or some other place for several weeks “making art” out of thin air. I just knew he was an artist that liked to draw and talk about strange things in his free time and was a walking encyclopedia of all the stones and decorative methods out there (he made me memorize all of them by the age of five). Whatever he was doing, looked like anything but a job.

The truth is, my dad works all the time, not because someone asked him to, but because that is simply how he functions. Sometimes, after a long day of working on a complex mode, standing on his feet for hours, I’ll find him alone, late at night, etching and making prints. When I tell him to take it easy and not work so hard, he answers that he is relaxing. In this sense, but not only, he is a true artist, in the literal sense of the word. Ars, from Latin, means “skilled work”. In a world where the ready-made or the mere concept has become such a staple of art and culture, we take skill for granted. My father, at the age of 73, still carves marble and makes every model, no matter how big, with his bare hands. In fact, he can make just about anything, from cabinets, to tables, to chandeliers and staircases. It was not until I started spending full days at the studio that I realized how much time and especially patience his practice entails. He has real, transferable skills, the same way old masters — those carpenters and carvers I read about in Hardy’s novels — could transmit their knowledge to the future generations. Except in his case, few young people want to dedicate their time and measured attention to learning this craft — and unfortunately, I’m not of great use with a mallet and a chisel. Yet, one of the main lessons he taught me, even before I began working for him, was “measure twice, cut once” a phrase I apply to everything (or try to.)

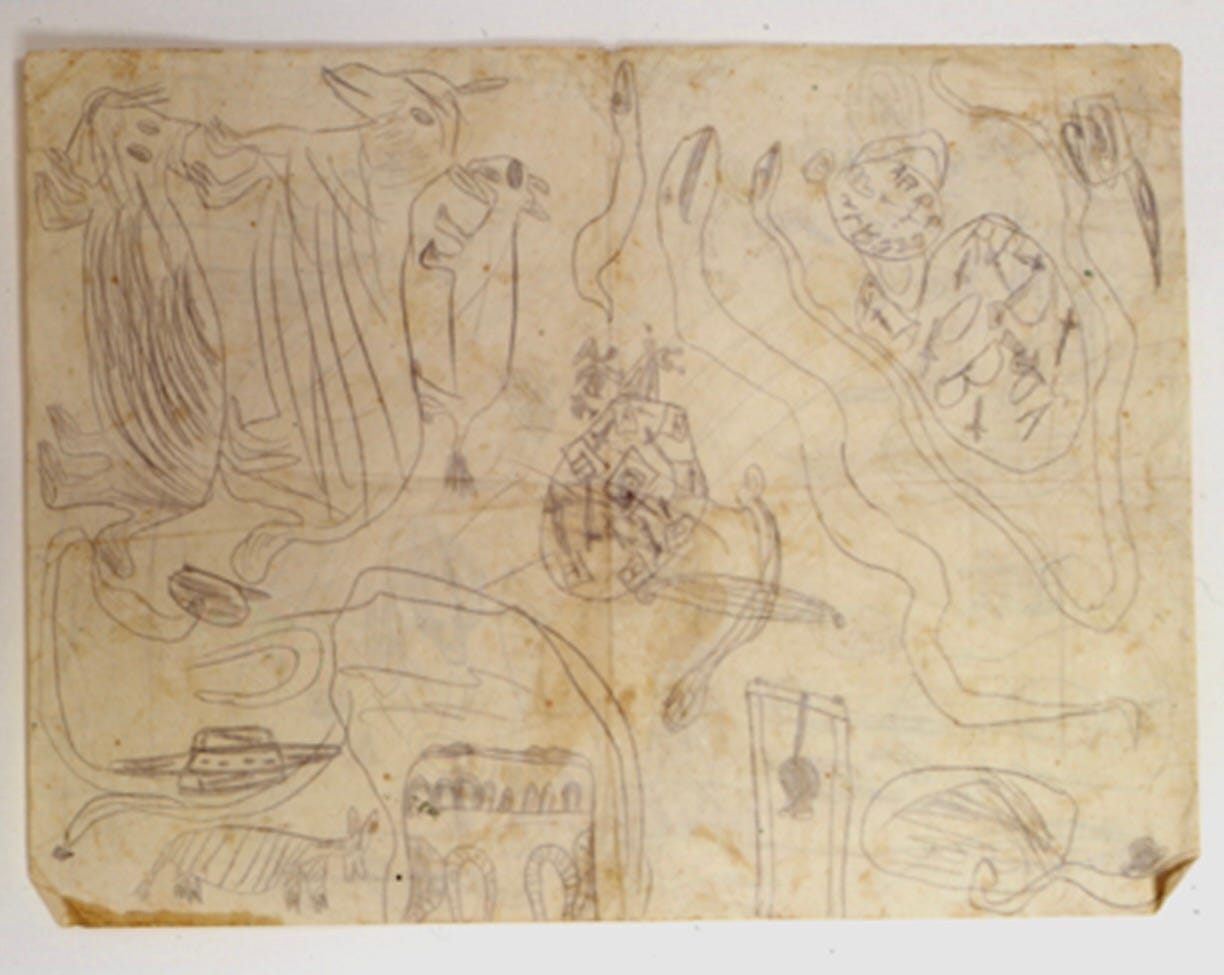

Time is truly at the center of all these reflections, because I have begun to perceive my father’s work through time and familiarize myself with all the phases his work has gone through. The other day, I was sorting through some works in the studio and stumbled upon Saint Clair’s drawings from when he was five years old, dating back to 1956. The paper was yellow and completely crumbled up. On it were fading lines depicting huge elephants along with a whole menagerie of animals, real or invented. My father was drawing since he could hold a pencil, and so many years later I can still see the same organic shapes and themes in his work today.

Working for him has given me a new understanding of his work, who he really is, and also what it means to be an artist. I no longer see his art as “just” sculptures, the way I did when I was little, but as the huge projects that began with quite pure ideas. I came to manage my dad’s studio because he was looking for a new assistant and who was better than I, having just lost my job and all aspirations in life? Jokes aside, I was quite enthusiastic about working for him because, quite honestly, it meant I could work from home and the hours I wanted which allowed me the time to write. I was coming in at quite an essential time because he has two shows coming up, one exactly a month from now in Zurich with the Tobias Mueller gallery and another in September with David Gill in London.

Here comes the part where I start explaining, and justifying by proxy, what I actually do. To people who don’t work with me or in the industry, it’s something I’ve often felt the need to do, which is one of the main caveats of working for my dad. There is a sort of prejudice against working for a family member, at least among people of my generation. I’m not exactly sure why that is exactly, although I can’t deny I haven’t held that prejudice myself. I suppose I worried about two things mainly. First, that by working for my father didn’t count as a “real” job because I wasn't being confronted with the widespread experience of corporate life, and therefore that no one would really respect me. Second, I was afraid of living under my father’s shadow and never having an existence of my own. These are, after all, not so unreasonable worries, yet once I pushed them aside and understood how equally demanding my current job was from the one I had in film production, I ceased to question it. The only difference between what I do now and my job in Paris — aside from the fact that the project produced is a sculpture and not a feature film — was that I could yell at my boss and be antisocial with far less consequences (still not recommended).

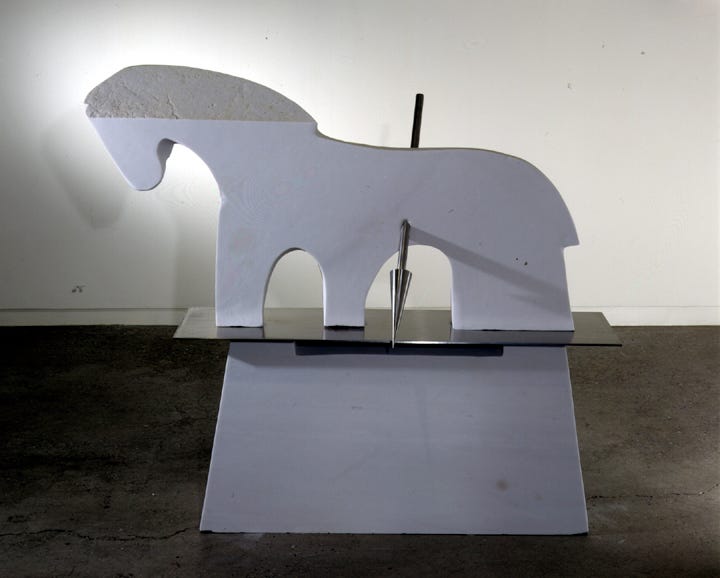

What I do for my father mainly consists of coordinating all the different actors that participate in the production of a large metal (usually bronze, copper or stainless steel) or stone sculpture. Mind you, I didn’t realize how complicated that process was until I began getting in contact with the foundries, technicians, galleries, curators, museums, clients, and shippers each stationed on a separate continent. Though I pride myself on being an organized Virgo, I definitely do not feel like I have everything under control, mainly because I don’t. There are too many contingencies and interferences for anyone to control the situation. Working in production management, whether in film or in art, is a great lesson for life: no matter how prepared you are, disaster is always unexpected. Another important aspect of my work is building the bases for his catalogue raisonné, which is basically the record of all the work he’s ever made. This is the kind of archival work I used to dream of doing back when I was studying History at university. I simply love filing, sue me! Of course, aside from filing, I get to perceive Saint Clair Cemin not as my father but as an artist belonging to a period in art history, and now evidently a precursor to so many sculptors and styles today. In these moments, I simply cannot deny the privilege I have of seeing a bit of history unravel before me.

You might still be wondering how I got to this satisfied feeling, especially since it is quite removed from my passion for storytelling, film, and theater. My astrologer would answer that with my ascendent in Pisces and my Jupiter ruled by Gemini, I am bound to having multiple careers and interests. If I am completely frank, I saw an opportunity and took it — beggars can't be choosers in this ill-fated economy. However, basing my explanation solely on the economic factor would be to downplay a long process of rebellion and reintegration — in short, the plain old “growing up” game. Worrying I might die in my father’s shadow and never succeed in my own endeavours if I don’t move to another country and toil til I finally have my big break is the sort of adolescent illusion that is necessary before diving into reality. I am not a coward for choosing the “easy route” of working for my dad. Courage never exists outside of its context, it is entirely dependent on the fear that must be surmounted. The reality is that rejecting something as meaningful and important as sustaining to your father’s legacy, only because of an invented principle is a real shame. Perhaps it was not my first choice, but part of growing up is learning that we seldom have the choice, and when we do, we must strive for the right thing. It’s A Wonderful Life definitely had an important impact on me, to say the least.

I sincerely believe that one cannot live a satisfactory life as long as one behaves according to what “others” will say. “Others” are a ghost once made-up by the undeveloped mind for some useful yet irrelevant reasons a long time ago. Living by your own rules does not mean living by no rules, it means trusting yourself enough to stick to the values you’d like to implement in your life. It is a tough exercise that requires many steps, the first being to set your pride or ego away. That in itself is a constant struggle, but that struggle, unlike for the bored Sisyphus, lightens each step of the way. Working for Saint Clair Cemin, my dad, has not only opened my eyes to a more refined and curious understanding of art and the art world, it has also helped me redefine my life.

There's the post I always wondered you might write. Well done! Only wish I could "Like" it several times.

I definitely want to hear more about this!