I’m dreaming of a British Countryside Summer

Pride and Prejudice and how I suddenly trapped myself into a niche

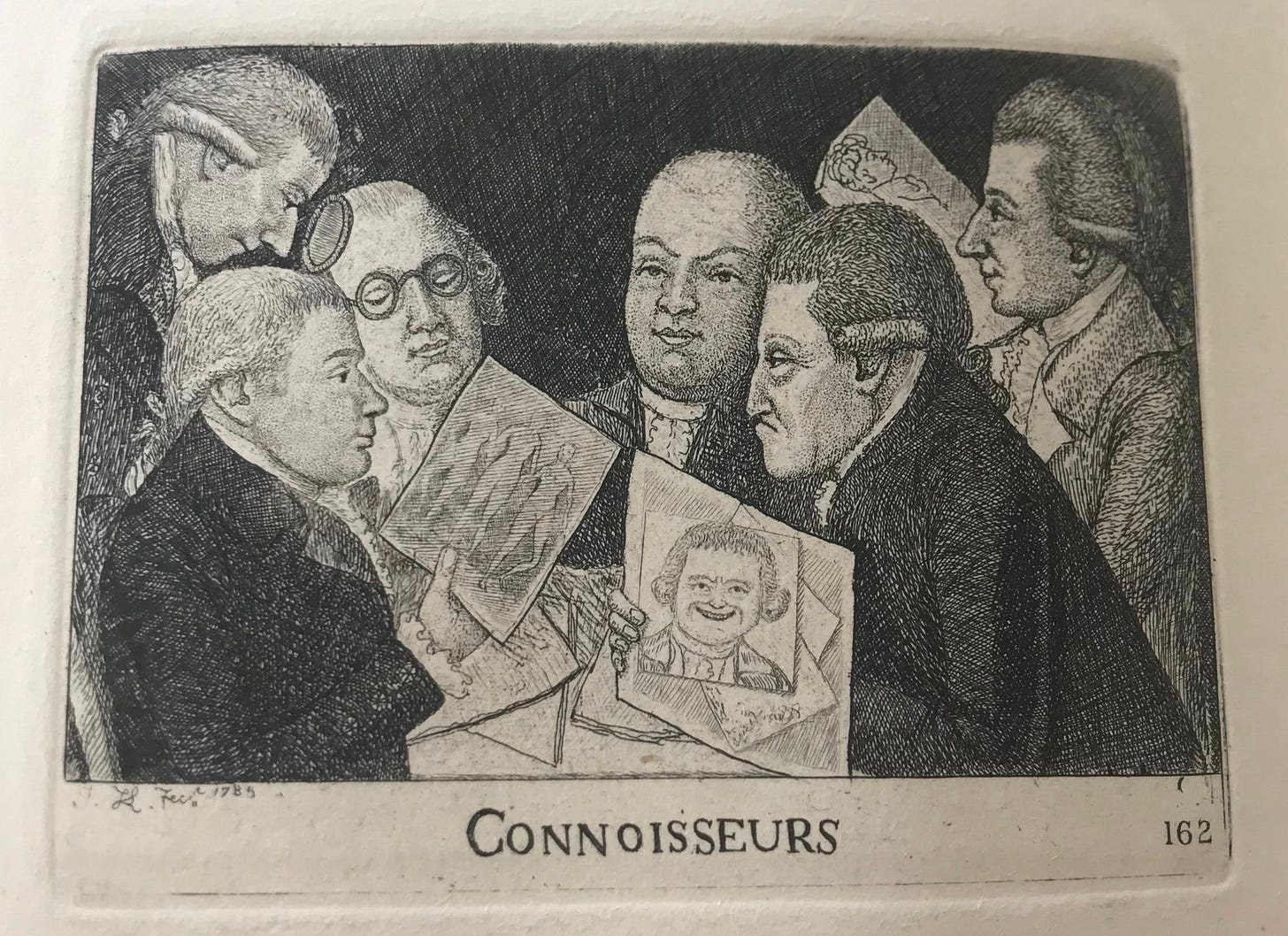

It’s funny how we choose to consume different types of media on the basis of our moods. Often those moods are prolonged into phases, and sometimes even mature into becoming our entire identity. I’m too volatile to have ever settled on a specific aesthetic or genre — which makes creating a social media persona quite a challenge. The god Niche, son of the gods Marketing and Public Relations, has become the leader of self-expression, turning internet users into dull caricatures of what they (used to) enjoy. Perhaps I am being too harsh; Niche didn’t choose to be born, nor to be deified — he exists despite himself. And I too, despite my rebellious stance on being different and being free, can be — and, to my great surprise and vexation, have been — typecast. After all, our society can’t breathe without a good system. The British Empire — its rules, regulations, systems, and categorizations — didn’t exist for nothing, and I am not as immune to its labels as I’d like to believe.

Yes, indeed, I am living the British fever dream. Or perhaps it is only by coincidence that I have chosen to read almost exclusively British literature and watch related films. In the past six months, I’ve read Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, The Mill on the Floss, Tess of the d’Urbervilles, To the Lighthouse, Dracula1, Liza of Lambeth, Jamaica Inn, and The Girls of Slender Means2. Though these books are hardly related in tone and atmosphere, ranging from Gothic horror to post-war London girls’ boarding house gossip, they are all great British classics. I believe what brings the whole aesthetic together was my watching Pride and Prejudice, A Room With a View, The Age of Innocence3, Howards End, The Remains of the Day, and recently Atonement in the past month.4

I believe the fascination — or rather, the current mood that’s been pushing me to immerse myself in this particular British-mansion atmosphere — comes from a deep, and phantasmagorical, nostalgia for my university years. I studied English Literature and History at the University of Edinburgh; until now, the best four years of my life. Back then, I had no particular interest in British culture, and Jane Austen bored me. I had chosen to go to that university for many reasons, not one relating to some dark academia aesthetic or to meet a prince or whatnot. Those images and references are as far as one could get from the experience I had in Edinburgh. Admittedly, there was a Quidditch team, but this was hardly the norm.

As you may have guessed, I was studying “classical” literature, but nobody called it that. We studied the canon from Chaucer to Yeats in our first two years and then were left to choose our preferred courses, none teaching books written after the 20th century. That was the curriculum. I chose to study those subjects, History included, because I wasn’t sure what I wanted to study in the first place, and I knew these would provide me with a general knowledge of all the other subjects that also interested me, such as philosophy, psychology, and theology. I ended up majoring in Intellectual History in my final year.

It was only when I moved back to the United States that I learned that the literature I had read was considered “classical.” That a book like Tess or even The Grapes of Wrath, written in 1939, would fall into that category came as an absolute shock to me. Classics, to me, had always been related to ancient Greece and Rome. It dawned upon me that literature itself had actually become a sort of internet niche, associated with a Neo-Tumblr girl aesthetic — less grim and more prim — or a more masculine, Infinite Jest and Dostoyevsky-centered pseudo-stoic rhetoric. These are the two main groups that immediately caught my eye when I joined Substack; blame the algorithm. So, only recently have I understood that enjoying Pride and Prejudice by Joe Wright was placing me by default in a category of people I never knew even existed until I started spending more time on the internet.

I find this nichification of literature to be a serious problem. As much as I understand and admire the — particularly Anglo-Saxon — culture of hyperspecialization, this tendency limits curiosity on a general level. An education system that is more focused on general knowledge, or culture générale — as it was in France, for instance — is based on the idea that there are some things everyone ought to know. I, unoriginally, believe that reading the canon of English literature is not just something people ought to do for education’s sake, but is a civic duty. These books introduce their readers to the way life used to be and open their hearts to empathy, sensibility, and critical thinking, which are all necessary in civic life. Qualifying these seminal books as “classical” makes them sound irrelevant, outdated, and inaccessible. Turning ‘classic’ literature into a niche is the same process as turning the idea of the nerd — that is, a curious individual — into a pejorative.

I am a proud nerd, though I cringe at the word. I’m a nerd and my recent obsession has been nineteenth and turn-of-the-century novels because I miss reading complex books that evoke many themes and ideas which I used to discuss in class. More so, I miss something I didn’t experience when I was in the UK: mingling with the British upper class, or some fantastical idea of it — something out of Saltburn. Though, at the time, none of this was my concern; I was living in the moment and thoroughly enjoying it. Perhaps I want to escape back to a time when the internet was not even a word, when writing was a serious endeavor, when love was not a plaything — a time when elegance, refinement, and order were prevalent. Yet, this vision — the one that Joe Wright and James Ivory depict — is a romanticization of those period pieces. As a historian, I know the harsh realities of the past. These books and films warp our imagination, make us want something that cannot exist. The ills of the internet, of these little niches, are but innocent offspring of these great illusions that we avidly consume for centuries. But what is life, if we’re not allowed to dream?

Irish, I know…

I recommend all these books; they’re genuinely great classics. Liza of Lambeth and The Girls of Slender Means are quite short and I thoroughly enjoyed both. Warning: Liza of Lambeth is quite heavy on dialect and takes some getting used to if you are not familiar with it.

I also read Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides (I recommend this too), My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh (this also), Confessions of a Mask by Yukio Mishima (this also), The Charterhouse of Parma by Stendhal (I do not recommend, as it is long and laborious despite being quite insightful about the Napoleonic period), The Women by Kristin Hannah (the subject is interesting but it feels like it is written for twelve-year-olds), Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar (I found it dull, uninspired, and self-indulgent). As you can see, it’s not all British — but still…

American, but the same vibe — and also based on a novel.

I recommend all these movies. I think they’re masterpieces of cinema, not just feel-good (or rather feel-bad-but-in-a-good-way?) big-budget Hollywood films.